As the saying goes, better late than never. That is especially true when providing notice of a claim or an occurrence to insurance companies. While the circumstances surrounding notice may be unique to each case, common reasons why a policyholder might encounter notice issues include missing policy evidence, sending notice to the wrong insurance company, a belief that they won’t be found liable, did not expect the liability would reach excess coverage, and many other reasons. Nevertheless, when possible, providing timely notice to insurers is critical to avoid issues that could delay or prohibit access to coverage. Our previous blog post, Who You Gonna Call (to Give Notice)?, gives some practical tips for preparing for notice and tracking follow up correspondence from insurers.

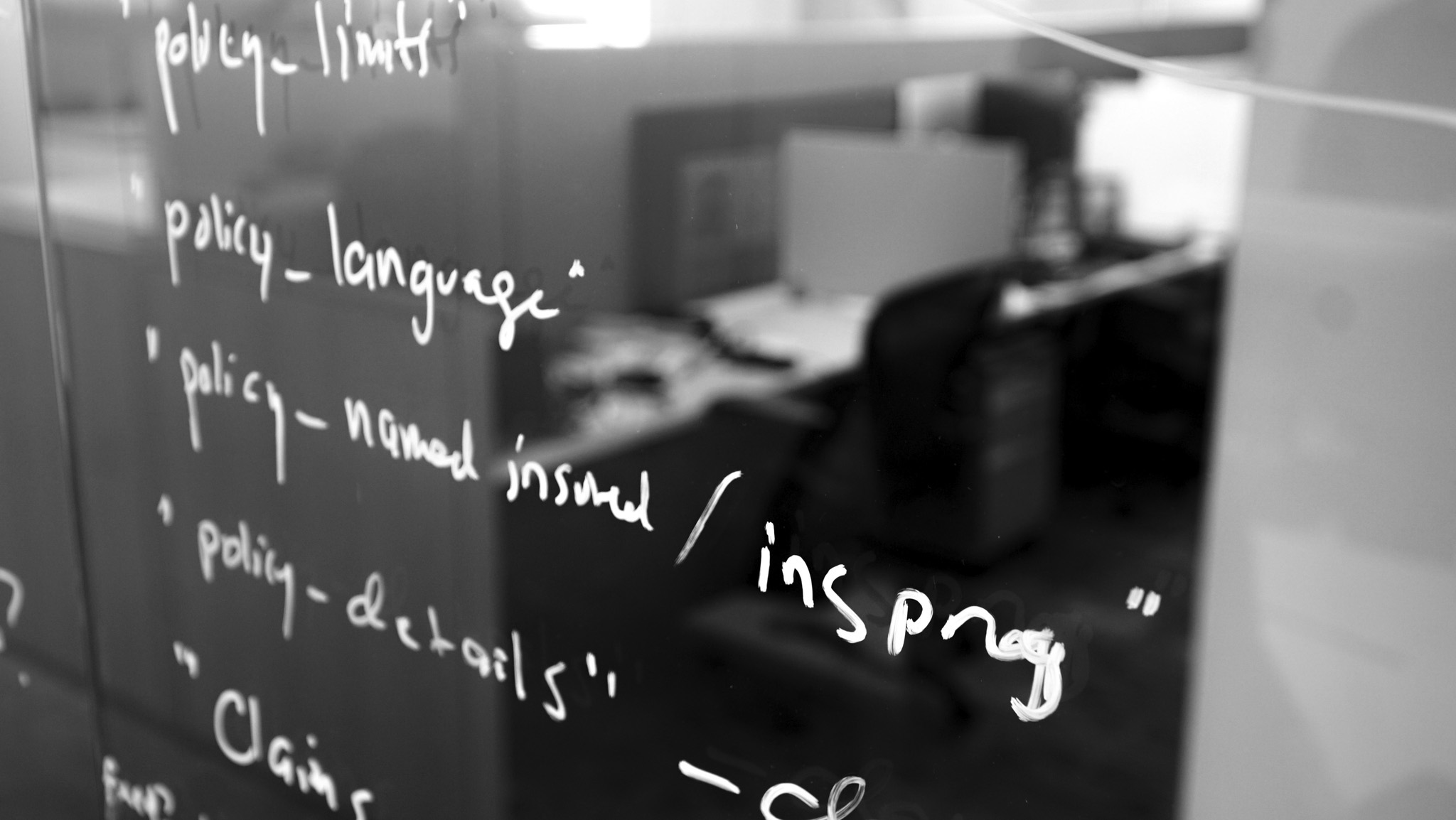

Nearly every insurance policy has a provision that provides information on when an insured should send notice. Why? Late notice can impair an insurer’s investigation and defense of a claim that they may be asked to pay to resolve. The many variations of notice language add to the complexity of the task. For instance, KCIC’s policy form language database has 50 variations of notice language for policies issued between 1951 and 2016. Below are the three variations of notice language that appear most frequently across KCIC’s analysis of over 400 standard forms.

Because both sides are governed by when and how to give notice by the terms of a policy, providing notice is usually not as easy as emailing an insurance company. Therefore, reviewing all of the policies to understand their notice language (preferably before a claim arises) is the first step in the notice process. Having access to a database of standard form language is especially useful to help to make an educated guess as to the notice requirement in the event a copy of the policy cannot be located. Next, we will take a closer look at the three most common types of notice language found in our review of standard forms.

“Reasonably Likely to Implicate Coverage” is the most common notice language found in umbrella or excess coverage according to our review of standard forms. For this type of language, a policy’s attachment point and the amount of forecasted liability could play a larger role in determining the requirements for timely notice. For example, a case under Illinois law found that the policyholder provided late notice because the estimate of their environmental liability, which they knew about up to six years prior to providing notice, would likely exhaust coverage underlying the excess policies in question, which attached as low as $6M (Household Int’l Inc. v. Liberty Mutual, 2001).

More commonly you find the “Immediate” notice language in umbrella or excess coverage according to our review of standard forms. Also, depending on the state, they can interpret the “immediate” stricter and require far quicker notice compared to other types of language. For example, in some cases, New York courts have found notice to be untimely under the “immediate” notice requirement even when it was provided within a month of the occurrence. Understanding the notice language in your policies before a claim arises becomes even more critical where “immediate” notice is required, especially in less forgiving states.

“As soon as practicable/possible” is the most common notice language found in primary coverage and the third most common notice language found in umbrella or excess coverage according to our review of standard forms. “As soon as practicable/possible” is generally considered to be more forgiving than “immediate”. For example, a New York case where notice was given seven months after the occurrence established that the phrase “as soon as practicable” was not as ironbound as “immediate” and that it was subject to the circumstances involved (Mighty Midgets Inc. v. Centennial, 1979). While New York is an example of a state that has stricter enforcement of the notice requirement, many states seem to assess the overall “reasonableness” of the notice rather than making large distinctions between common types of notice language.

In such states, the “notice-prejudice” rule, which prevents insurers from denying a policyholder’s claim solely on the basis of delayed notice, may come into play. Like the notice requirement, the application of “notice-prejudice” can also vary among states. For example, some states require the insurer to prove prejudice, others require the insured to disprove prejudice, while others only require a “probability of prejudice”.

To add to the complexity, in a few instances we have found within a policy there is more than one type of notice language. Most commonly, we find “reasonably likely to implicate coverage” language alongside “immediate” or “as soon as practicable/possible”. This can have different implications for a policyholder’s notice requirement depending on the state and how the policy combines the different types of language. For example, a case in Georgia with a “reasonably likely to implicate” provision found that a policyholder’s notice, given 13 months after evidence of loss, was unreasonable because there was a second notice provision that stipulated the notice should be “immediate” (Briggs & Stratton v. Royal Globe, 1999). Cases like this underline the importance of doing a thorough language review.

Perhaps almost as important as when to provide notice is to whom to provide it. The insurance company is sent over 70% of the policy forms in our database with notice language required. Other options include: to the company or any of its authorized representatives, and to the agent or broker. We find that general liability policies issued over the past decade or so, even those in excess layers, often have a specific address to which we send the notice. Capturing or otherwise storing this information during the initial policy intake process might save you time when you must provide notice of claim.

Insureds and insurers have litigated notice issues for an exceptionally long time and will continue to do so. Whether an insured is found to have provided notice on time often comes down to the policy language at issue and the relevant state law, though some states take stricter interpretations on either side of the issue. Policyholders would do well to become acquainted with their policy language and what legal precedents might apply to it prior to any claims arising.

Never miss a post. Get Risky Business tips and insights delivered right to your inbox.

Nick Sochurek has extensive experience in leading complex insurance policy reviews and analysis for a variety of corporate policyholders using relational database technology.

Learn More About Nicholas